Furnishing to a Construction Project in Florida? Make Sure You Serve the Florida Notice to Owner

If you are furnishing to a construction project in Florida, you should bookmark this post! This post is dedicated to serving preliminary notices in Florida and includes pertinent deadlines and requirements.

You’ve Got 45 Days

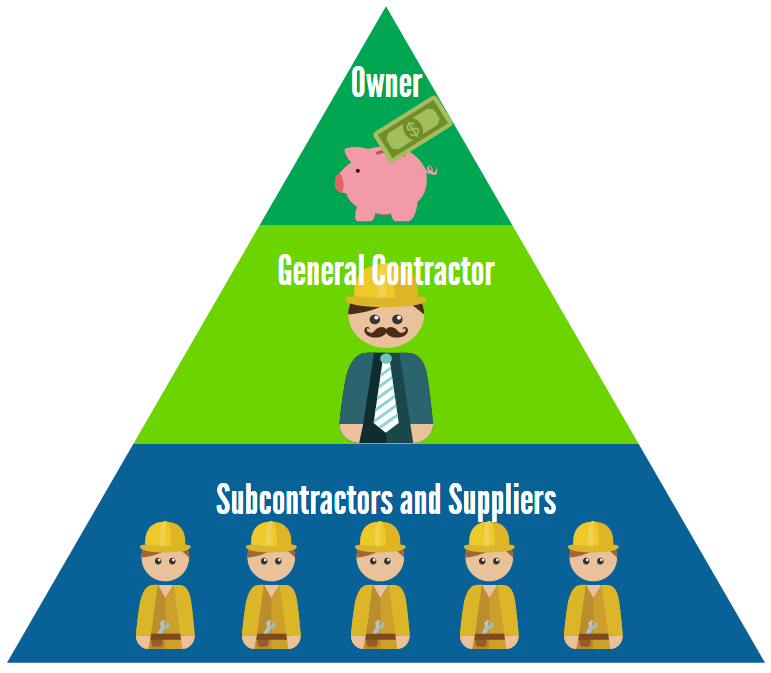

In Florida, the private preliminary notice is also referred to as the Notice to Owner (“NTO”). Those furnishing to a private project in Florida should serve notice upon the owner, and upon all parties in the contractual chain between their customer and the owner, prior to or within 45 days from first furnishing materials or services.

In Florida, the preliminary notice must be received within the 45-day period, which means that simply mailing it on the 45th day is insufficient. If you supply specially fabricated materials, your clock begins sooner, and the notice must be served prior to or within 45 days from the date fabrication begins.

Florida NTO Tidbits

- It’s recommended you also serve a copy of the notice upon the lender when they are listed on the Notice of Commencement.

- If you provide materials or services to a leasehold property, serve demand upon the lessor for a copy of the provisions in the lease that prohibit a lien against the property. If a copy is not provided to the claimant, the lessor’s property may be subject to a lien, rather than the claimant being limited to liening the leasehold interest.

- On residential (single- or multiple-family dwellings of up to and including four units) improvements, a prime contractor must include a statutory notice provision in their contract.

Little known fact: When contracting directly with the owner on a private project, no notice is required. Keep in mind, just because it isn’t required doesn’t mean that serving a notice won’t help to get you paid. NCS Best Practice is to serve a notice on every project.

How Should I Serve My Notice?

With a side of rice and fresh veggies! Kidding, only kidding. I recommend serving the Notice to Owner via certified mail but Florida statute dedicates an entire section of their statute to the “Manner of serving notices and other instruments.”

Here’s a small snippet

713.18 Manner of serving notices and other instruments. —

(1) Service of notices, claims of lien, affidavits, assignments, and other instruments permitted or required under this part, or copies thereof when so permitted or required, unless otherwise specifically provided in this part, must be made by one of the following methods:

(a) By actual delivery to the person to be served; if a partnership, to one of the partners; if a corporation, to an officer, director, managing agent, or business agent; or, if a limited liability company, to a member or manager.

(b) By common carrier delivery service or by registered, Global Express Guaranteed, or certified mail, with postage or shipping paid by the sender and with evidence of delivery, which may be in an electronic format.

(c) By posting on the site of the improvement if service as provided by paragraph (a) or paragraph (b) cannot be accomplished.

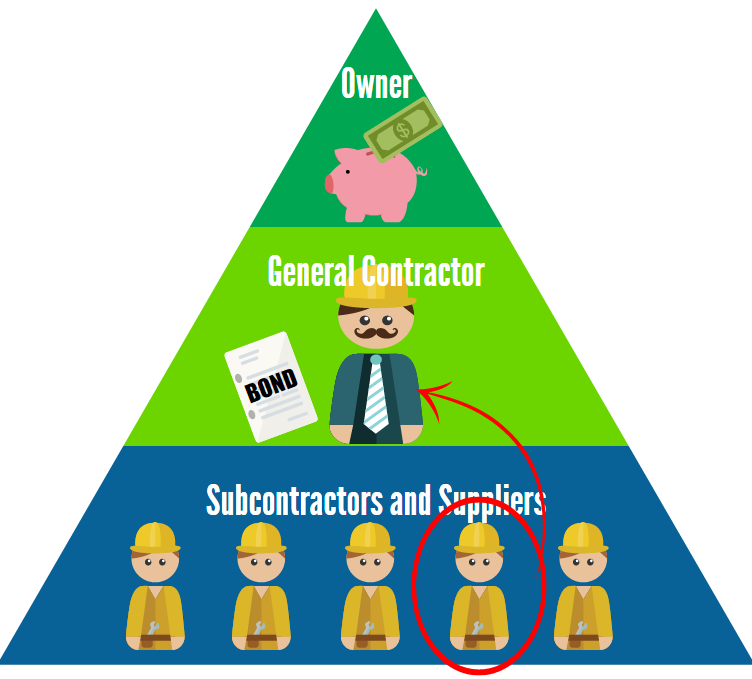

Florida Notice to Contractor – Public Projects

If you are furnishing to a public project, there are only a few differences than when furnishing to a private project. Of course, for public projects, you are securing your right to make a claim against the bond, as mechanic’s lien rights are not available on public projects. The public notice is referred to as a Notice to Contractor instead of a Notice to Owner. Plus:

- If you are contracting with the owner on a public project, bond claim rights are unavailable.

- If you are contracting with the general contractor on a public project, no notice is required.

- If you are furnishing to a Department of Transportation project, you should serve the notice upon the prime contractor prior to or within 90 days from first furnishing.

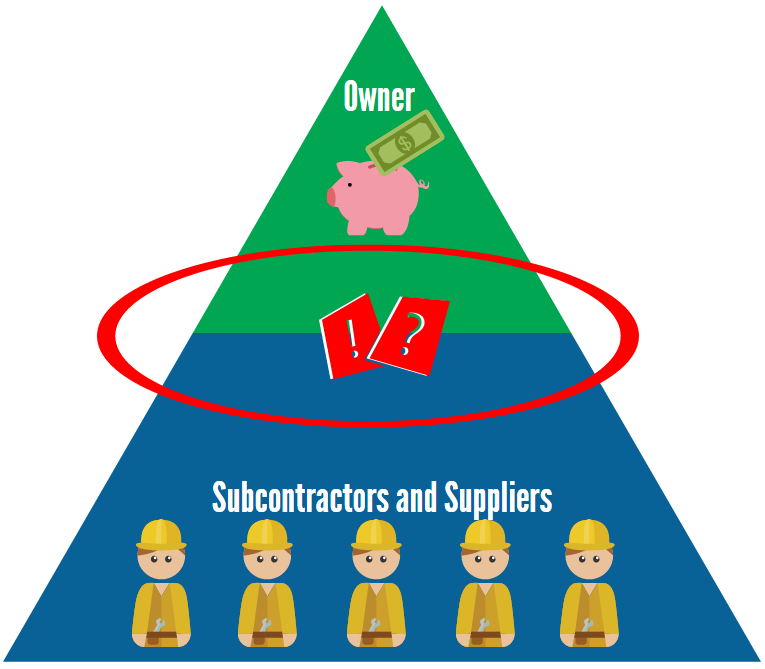

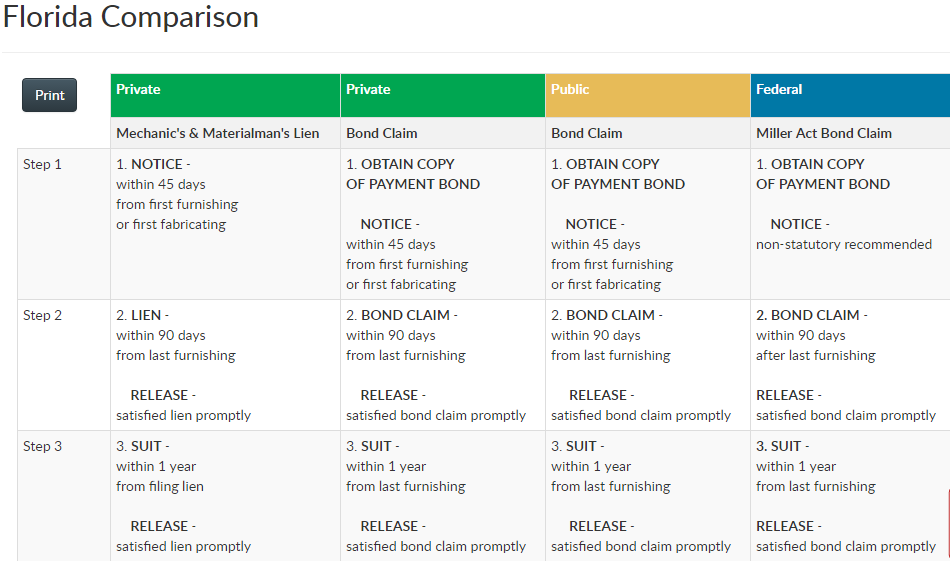

Love a Quick Comparison

I’m visual and love charts and graphs explaining information, so here’s a comparison we provide to subscribers of The National Lien Digest.

As always, please remember that this information is not an exhaustive list of all things Florida; rather, it’s an outline of the steps necessary to secure your rights.