Arbitration, Mediation, Lawsuit – What’s the Difference?

Over the holiday break, I spent some time reading articles I’ve (shamefully) had bookmarked for way too long. One of these articles reviewed the pros & cons of arbitration in construction disputes, although for me, it better explained the similarities and differences of arbitration and a lawsuit.

Construction Arbitration: The Pros and Cons by Jason Strickland of Ward and Smith, P.A.

Arbitration vs. Mediation vs. Lawsuit

I don’t think I have ever confused a lawsuit with arbitration or mediation, but I have certainly confused arbitration with mediation. Here are key features explained by Strickland:

“Mediation is a settlement conference in which the parties meet (typically in person) and use a third-party neutral to act as a settlement facilitator. The third-party neutral is called the mediator.”

It’s important to note, the mediator can’t force a settlement – which I didn’t know. I assumed the mediator has the same powers that an arbitrator has.

“A lawsuit is conducted in a court of law and usually is initiated by a plaintiff filing a complaint, in which the plaintiff will ask for some form of relief from the defendant.”

In the NCS world, a lawsuit is often referred to as “suit to enforce…” a lien or bond claim.

Now, this explanation of arbitration is new to me, in part:

“Arbitration is essentially a lawsuit but without court involvement.”

Wow. “Arbitration is essentially a lawsuit but without court involvement.” Yes! That’s a great explanation. Why? Because arbitration is binding, just like a legal decision.

Mind. Blown.

“The parties agree… to submit their dispute to arbitration rather than to pursue a lawsuit in court. The parties’ agreement gives the arbitrator the power to issue a decision as to the parties’ rights and obligations, and such decision will be legally binding on all parties. Thus, arbitration is very different from mediation because the third-party neutral provides a legally binding decision. However, arbitration is not mutually exclusive with mediation. In many cases, parties will have a dispute resolution provision in their contract that will allow, or require, the parties to mediate first, and if the mediation is unsuccessful, to then submit their dispute to arbitration.” – Jason Strickland

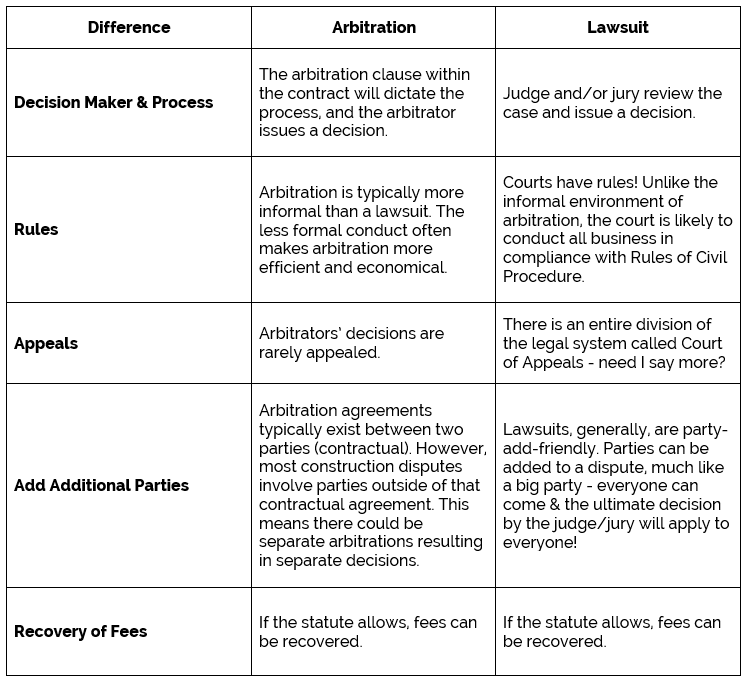

The Differences (Pros & Cons) Between Arbitration and Lawsuits

Strickland reviews several differences between arbitration and a lawsuit. Here’s a quick table to break down Strickland’s points.

So, who wins? Arbitration or Lawsuit?

Obviously, it will depend on your circumstances and contractual language, but both options have their pros & cons. A key benefit in arbitration is the efficiency; with a less formal environment and the rarity of appeal, it can prevent a case from dragging on. On the flip side, construction disputes typically involve a myriad of parties, which can be easier to accommodate within a court/lawsuit setting.